Years ago, when I was a magazine editor in New York, I learned that “white space” was integral to good design.

The graphic artists I worked with always opted for maximum “white,” or blank space around images and text for a clean, visually appealing layout. In order to give the content room to breathe, the writers were often asked to trim some of their beloved copy, which they weren’t always happy about.

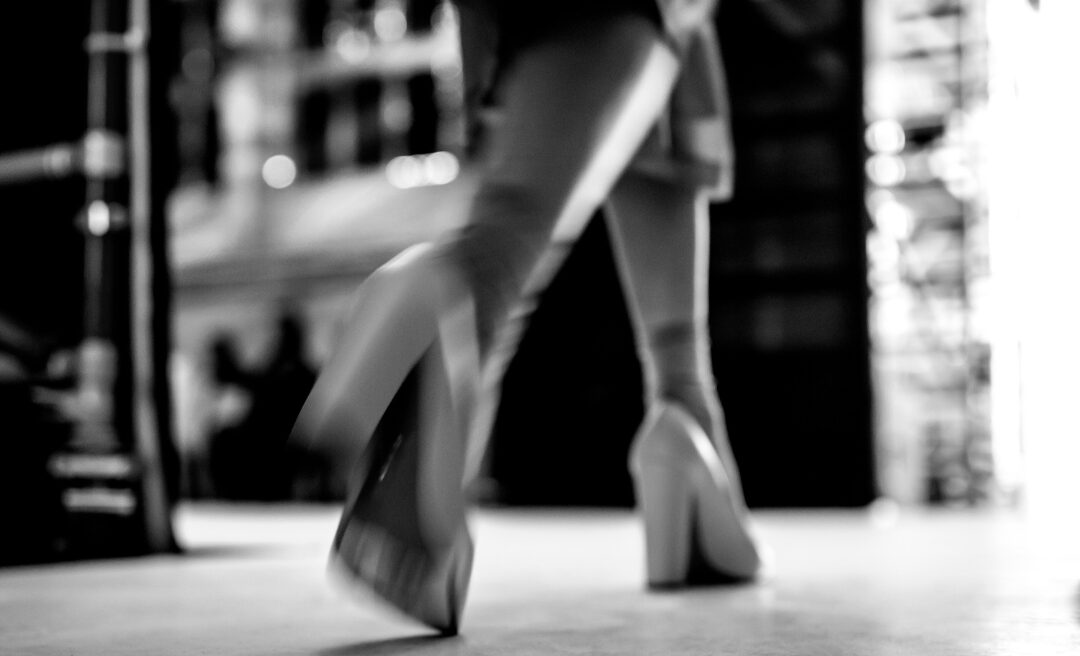

One of my jobs was to strike a compromise between story and design: to churn out pages that were beautiful to look at and easy to read, but meaty enough to keep our audience absorbed. Style versus substance, flirtation versus follow-through. A magazine required both, and as a writer and an editor, I enjoyed the delicate balancing act.

Little did I know it then, but I was discovering the Japanese concept of Ma, or the importance of negative space. My mother-in-law, Elaine, recently mentioned it during a lesson in ikebana, the Japanese art of flowering arranging. She is a master instructor and just started teaching me.

Ma can be described as the empty space between things that helps to balance and define the whole. In ikebana, gaps between the flowers and other natural materials are emphasized to create a focal point, movement and emotion. Ma can also be the empty space in a painting or photograph, the silence between the notes in a song, the pause between words in a poem read aloud, and yes, the white space between elements on a magazine page. The idea is that a harmony between what’s there and what isn’t can deepen the overall experience and meaning of something.

According to Ma, everything in life is held in place by what is or isn’t there.

In The Art of Looking Sideways, author Alan Fletcher wrote, “Cézanne painted and modeled space. Giacometti sculpted by ‘taking the fat’ off space. Mallarmé conceived poems with absences as well as words. Ralph Richardson asserted that acting lay in pauses…and Isaac Stern described music as ‘that little bit between each note—silences which give the form.’ ”

In other words, space is substance.

Space is also energetic potential. What you project into an empty space—whether it’s material, physical, sensual or spiritual—shapes the experience of anyone who engages with it. For example, a generous space can allow freedom of movement and breath, while a tighter space can unify or restrain.

This theory also applies to human relationships. Between every two people is a space where positive or negative energy flows. Some of the most powerful things happen within that space.

Dave Matthews touched on this idea in his beautiful and complex song, “The Space Between.” He once said the lyrics (“The space between the tears we cry is the laughter [that] keeps us coming back for more”) express “what life is about: trying to bridge the gap that’s between us.”

According to Ma, everything in life is held in place by what is or isn’t there. Without loss, emptiness or separation we would not experience connection, fulfillment or joy. We also wouldn’t fully recognize how important something or someone is to us. Life requires us to create interruptions or absences that allow for differences to be reconciled, understanding to deepen, and opportunities to emerge.

During the pandemic, we became all too aware of the space that exists between us and others—six feet of it, to be exact. For many of us, distancing was hard. But it also made us grateful for our loved ones, as we longed to be physically close to them once again. Many of us did a lot of thinking and reprioritizing while in quarantine. We found creative ways to bridge the painful separations. But we also let some connections lapse and some gaps widen. And that’s OK too. Putting distance between things is essential for living—and appreciating life.

Midlife is the perfect time to be conscious about how you create and react to the spaces around you. As I get older, I’m getting better at stepping back and analyzing what is needed—or not needed—in a moment or situation: When to talk, when to be silent. When to take action, when to take a beat. Sometimes it’s important to pull people closer, other times it’s best to give them space (as any parent of a teenager knows). Some days, I gain energy and inspiration from socializing with a roomful of people. Other days, I require solitude in order to recharge and reflect.

Putting distance between things is essential for living—and appreciating life.

Just as I once relished the dance between white space and words, arranging elements on a magazine page to make them more meaningful, I’m now appreciating the distances between chrysanthemums and camellias, pussy willows and plum blossoms (thanks, Elaine). But more important, I’m becoming more aware of the necessary Ma—the spaces, or pauses, or whatever you want to call them—that cannot be seen, only profoundly felt.